|

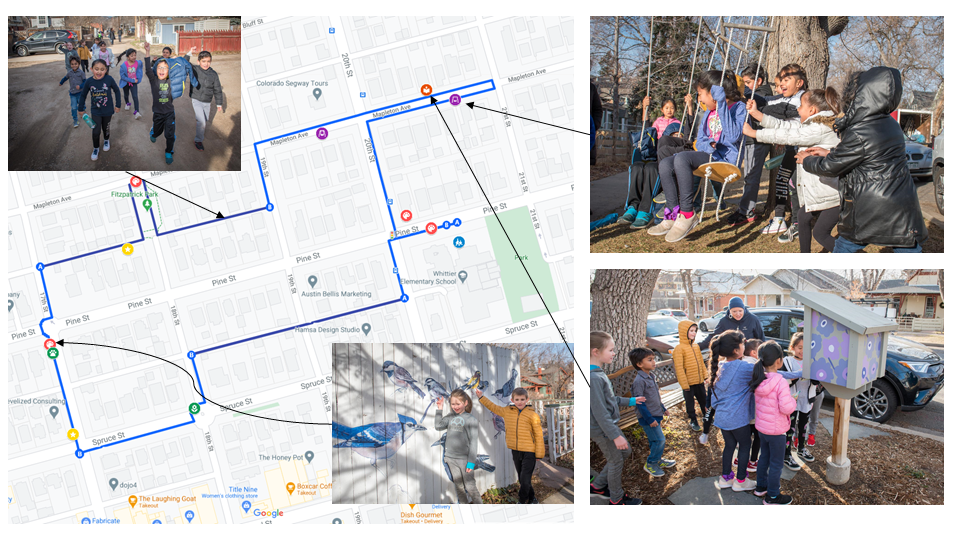

By Darcy Kitching In March 2019, Growing Up Boulder invited me to take a group of first graders on a walk. The class of curious and confident English language learners had helped develop the country’s first child-friendly city map, and I met them at their school to explore a fun walking route we would share with local families in the digital version of the map. Our on-foot exploration led to some unexpected discoveries. My young companions turned out to be urban paleontologists of a sort, unearthing the bones of child-friendly places and an actual dinosaur that sparked my own imagination. As a mother, a child-friendly cities researcher, and an urban planner specializing in walkability, I think I pay more attention than most to the little details that compel people to get outdoors and actively explore their environments, but the 15 first graders I nominally guided on our walk showed me much more than I showed them. As we set out with their three teachers on our one-mile route, I pointed out the “leading pedestrian interval” crosswalk signal integrated into the four-way stop light near the school, which gives people crossing the street a head start when the light turns green. I brought their attention to the wide sidewalks that made it easy for us to explore together, and as we ventured down an alleyway to a pocket park nearby, I asked them to notice the lack of cars and the sense of safety that affords. But the pedestrian-friendly infrastructure in the school’s historic Boulder neighborhood simply allowed us to relax and enjoy the sights along our walk. It supported our real mission: to find out what made this particular area special. The first feature that caught the students’ attention was a metal sculpture of a buffalo in the front yard of a nearby house. They stood beside it for a photo, then ran down the sidewalk to two swings hanging from a tree in the parkway strip of grass between the sidewalk and the street. The students took turns pushing each other on the swings, gushing with enthusiasm. We found other delights in the public right-of-way along our route, including a Little Free Library with a bench for passersby, a tire swing, gardens with places to rest, creative rock patterns, artwork painted and mounted onto fences, and a series of decorative tiles set into the sidewalk. As we turned onto a dirt alley, several of the students ran, chanting, “Mex-i-co! Mex-i-co!” When I asked what they meant, one student told me that the narrow dirt lane reminded her of visiting her family members in that country. Her delight spread, and soon they were all chanting and laughing together. I captured their enthusiasm along the way and led them to what I had thought was the most interesting local feature: a tiny plaza featuring a color-coordinated chicken coop and Little Free Library, with a bench and lots of art. While I adored what the homeowners had offered their community by developing a colorful little resting place in the right of way, it was their flock of silkie chickens and a towering spruce tree that attracted the children. I was admiring the fluffy birds with some of the students when I heard a shout from the tree behind me: “Hey, look - a dinosaur!”  I spun around and saw several children squatting and pointing, holding up the low branches of the spruce tree. I bent down and looked, too. There, in a clearing beneath the tree, was a brontosaurus beaming at us. I realized that, as sensitive as I thought I had been to children’s perspectives and interests in their environments, I never would have lifted up those branches myself. The children happily and without question explored every part of the neighborhood accessible to them, exemplifying the concept Dr. Catherine O’Brien has called “footprints of delight.” With so many enchanting features to explore, it was no wonder the first graders kept walking, running, and even doing gymnastics in the neighborhood park for more than half an hour on our journey with no signs of fatigue or boredom. My thoughts have returned to the dinosaur under the tree repeatedly since my walk with the students. I started reflecting on the dinosaur as a symbol of the hidden charms of the public realm and what it takes to intentionally create points of interest in places without robbing them of their mystery and delight. I thought about other child-friendly walks I had led and the “dinosaurs” the participants had gravitated toward, including art of all kinds, sculptural rocks, pools of shade, interesting places to rest, and even a bike rack that could be climbed through in a way I hadn’t imagined.

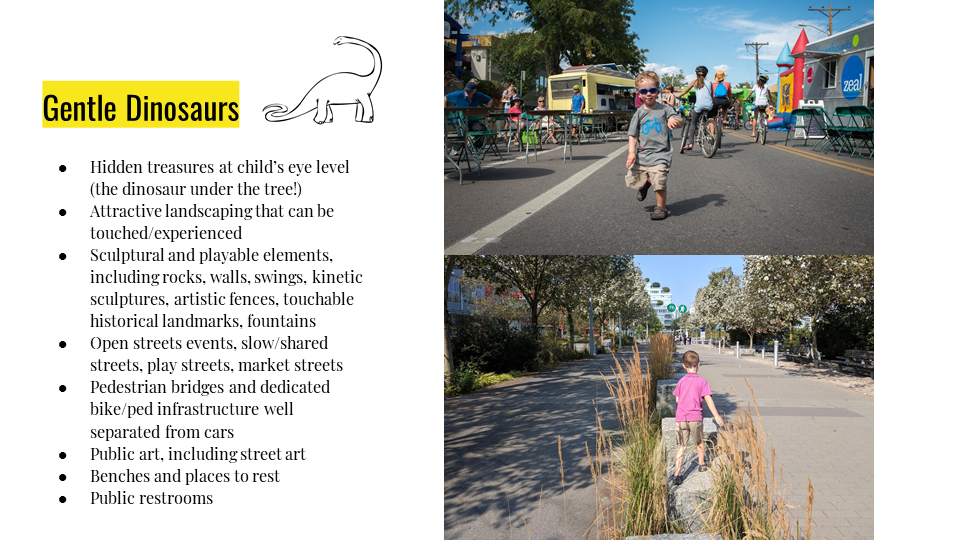

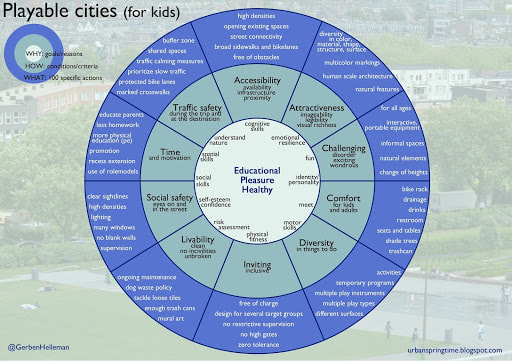

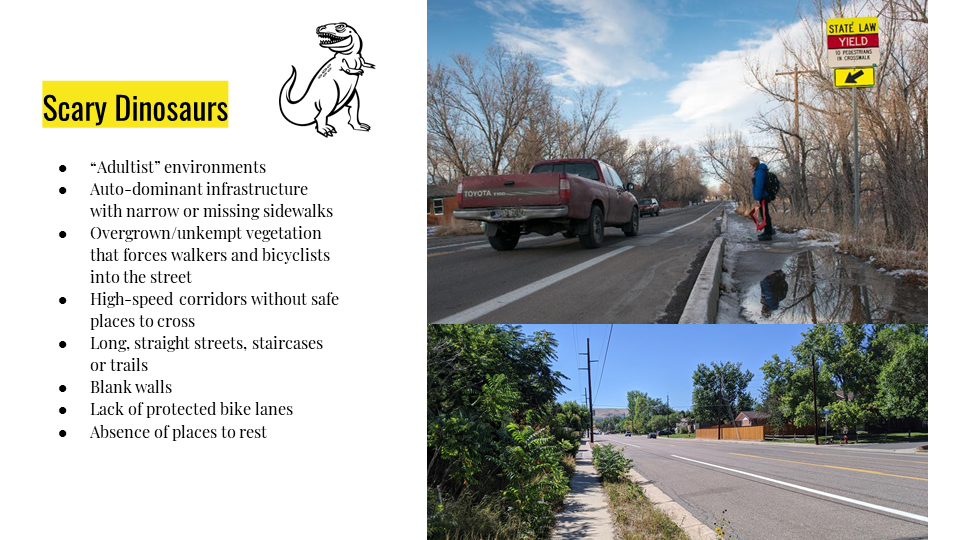

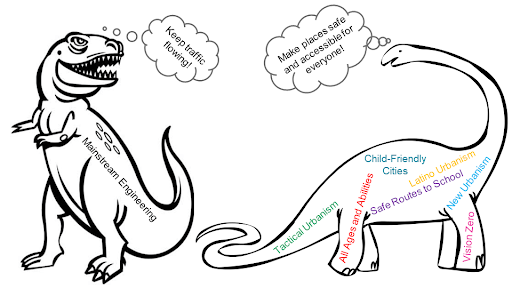

Reflecting on experiences with my 8-year-old son and thinking about principles of creative, people-friendly urban design, I identified both small and sizable “gentle dinosaurs,” from hidden treasures only a person close to the ground could find, to the amenities that support walking, including comfortable places to rest and accessible public toilets. The list above includes eight categories of “gentle dinosaurs” that can be implemented from the bottom up, by artists, individuals, organizations, and municipalities with hands-on community engagement. Even large-scale changes to the public realm can qualify as “gentle dinosaurs” - after all, brontosauri were massive creatures up to 75 feet long! I remembered the downtown Boulder open streets event we participated in when my son was 2 years old (top picture above), which featured food trucks, entertainment, activities, and open space for walking and rolling. And whenever we visit his grandparents in Vancouver, Canada, my son can walk for miles on the wonderfully child-friendly separated bike and pedestrian paths throughout the city (bottom picture above), where wide pathways, natural landscaping and climbable features make walking with a child effortless and fun. For adult caregivers, “gentle dinosaurs” also offer the enormous benefits of reducing stress and inspiring play. Not having to protect children from traffic and other hazards allows us to relax and simply enjoy our time outdoors. Dutch researcher Gerben Helleman captured the essence of such “gentle dinosaurs” in his work on “playable cities.” In the diagram above, he links the benefits of creating playable places with 100 specific actions that inspire and support play in urban environments, including accessibility - the availability and proximity of walkable infrastructure - and amenities that are inviting, inclusive, diverse, and safe. On the other end of the spectrum, “scary dinosaurs” tend to dominate public space in North America, creating decidedly “adultist” environments, as described by researchers Meghan Cope and Brian Lee. “Scary dinosaurs” are characterized by size and speed: they are built for people traveling in cars, attending to distant goals rather than near and present experiences. Like the T. Rex once did, “scary dinosaurs” tend to clear everything in their path, leaving behind inhospitable environments for smaller and slower-moving inhabitants. A few years ago, I worked with GUB and students at a Boulder middle school to identify barriers to walking and biking to school. The students pointed out how the lack of sidewalks, drainage, and safe crossings near the school made it too hard to travel actively. I witnessed several cars and trucks go by without yielding as a student waited at a crosswalk (top picture above). Speeding traffic is an obvious “scary dinosaur,” but the street design that enables it can also be classified that way. Long, straight arterial roads without any designated crossings facilitate speeding and inhibit walking and biking. In many areas, students have to cross the types of roads pictured above (bottom) to get to school, putting them at great risk. Places full of “scary dinosaurs” are also psychologically exhausting. It just isn’t fun or interesting to walk alongside blank walls, on uninterrupted concrete, or in places that lack shade and human-scaled amenities. For people dependent on public transit, walking, and bicycling, “scary dinosaurs” make getting around uncomfortable, uninspiring, and dangerous. Even though “scary dinosaurs” are pretty prominent in our everyday lives - owing to the dominance of mainstream traffic engineering and its goal of keeping cars flowing - there is a veritable rainbow coalition of people and organizations working to increase the presence of “gentle dinosaurs” in American cities and towns. Initiatives such as UNICEF’s Child-Friendly Cities and the international Vision Zero network are inspiring new approaches to ensuring that people of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds can walk and roll safely, in environments that support their well-being.

As those first graders who discovered the brontosaurus under the spruce tree taught me, the supportive infrastructure that makes walking easy paves the way for deeper exploration. Those students felt safe enough to squat down and peek under the tree, to cartwheel in a pocket park, to jump into a swing just a few feet from the street. Slow traffic speeds, wide sidewalks, and places to rest made discovering all of the special things in the neighborhood possible. And neighborhood residents had cultivated a culture of creativity, where just about every property offered something interesting to explore. Ask yourself, “Where are the dinosaurs?,” and go looking for them in your own community. What do you notice? Where might “scary dinosaurs” be tamed and “gentle dinosaurs” be encouraged? We can all breed “gentle dinosaurs” right where we live by inviting creative expression and exploration in the public right of way and working with our local governments and organizations to create child-friendly streets, eventually flipping the proportions of “gentle dinosaurs” and “scary dinosaurs” in our cities. After all, back in the Jurassic period, plant-eating dinosaurs outnumbered carnivores!

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

This Growing Up Boulder blog is a place for GUB leaders and partners to share their thoughts about child and youth participatory planning and child-friendly cities. Enjoy!

|

*Growing Up Boulder (GUB) is a nonprofit program leading Boulder's child friendly city initiative. GUB is fiscally sponsored by the Colorado Nonprofit Development Center (CNDC), EIN: 84-1493585. Since 2009, GUB has worked with over 8,000 local children and youth on more than 100 projects and reached more than 2.5 million people globally.

© COPYRIGHT 2015. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.