by Kai, a 14-year-old from Boulder, CO, living in a town outside Tel Aviv, Israel I was asked to write about the differences I’ve experienced as a kid living in America vs living in Israel. In particular, the differences in independent mobility and freedom. The one rule in Israel against kids doing whatever they want, whenever they want, without any supervision, is the rule that kids ages 9 and younger can’t cross the street without an adult. It’s got something to do with the fact that distance and motion perception isn’t fully formed until age nine, so they have a bigger chance of getting hit by cars. Other than that though, kids in Israel have much more freedom than they do in America. Here are some examples:

Last week, my eight year old sister went to her friend’s house at eight o’clock at night on a school night to bake a cake. She and her friends had planned that activity in school, and did not tell the parents it was happening until about an hour before they wanted to leave. We picked my sister up at 9:30pm, after the kids ate the chocolate cake they baked, with ice cream on top. A couple days ago, my eleven year old brother was invited to a trampoline park with his friend. Nobody could drive them there, so they took the bus. They both have their own bus passes, and took the public bus to the next town so they could go to the trampoline park. My friends and I are all 13 or 14 years old. We’ve taken the train to Tel Aviv (one of the main cities in Israel) a bunch of times. We get to the station, walk across town, and go to this huge mall. We stay there for a few hours, and usually come home at around nine at night. When I lived in America, there were only a few places I was allowed to go to without my parents. In many of these places, someone would ask me where my parents were and why I was there alone. Coffee shops are a good example. In Boulder, if I walked to Ozo Coffee without my parents, the people working there would more often than not ask why I wasn’t there with my parents. In Israel, on the other hand, it’s unusual not to see a group of ten year old kids sitting at a coffee shop or even restaurant without parental supervision. Because I live in a small town, you can get almost anywhere by walking or biking. Most kids have their own bikes. If they don't, they can just walk everywhere. Also, most people in Israel have their own bus pass. You can get it at a really young age and use it for the buses, trains, and the entire public transport system. Even if you’re a kid, you can get almost everywhere in Israel as long as you have your bus pass. It even has your picture on the back. It’s perfectly normal here to walk home by yourself from a friend's house at 9 o’clock on a school night. It’s also perfectly normal for your friends to take you with them to wherever they're going that day, and then drop you off at home at 10:00 pm. Probably the biggest difference between living in Israel and America is school. School here ends around 1:30pm, so you don't eat lunch at school. You have a snack at 10am (called “the ten o’clock meal”) and then you go home for lunch. The whole afternoon is free for after school activities. One of those activities is a youth group that almost everybody is in. There are a bunch of different ones all throughout Israel. The groups are run by kids in 10th - 12th grade, and they’re the counselors for kids in 3rd - 9th grade. I think there's like one or two adults involved in the youth group, but you never see them at the activities, and they just help with funding and running the program. I’ve never actually seen them at one of our weekly meetings. In Israel, the kids are given more responsibilities and more trust when it comes to those responsibilities because they're given the chance to take on leadership positions at a really young age. Then, they are better prepared when they have to be leaders in adulthood. The way kids are in general is very different here than in America for not only that reason, but also because they have a lot more freedom. Parents here also aren’t as hovering in Israel. This can be good and bad because sometimes it can be fun to be at your friend's house, and even though their parents are home, you can do whatever you want. Sometimes it's also not fun because if you want to go somewhere, there might not be anyone who can drive you. Then you have to figure everything out on your own. In most Israeli families, both parents work. That means they’re usually not home during the afternoons. Any kids ten and older are allowed to be at home alone, so the parents only stay home if they have little kids. Kids who are old enough to go to preschool can stay in after-school care. That program continues until kids are ten years old. After that, the kids just hang out at home, with friends, or at after school activities until their parents get back from work. I don’t like to judge which country is better. In my opinion, both America and Israel have their pluses and minuses when it comes to independent mobility and freedom. I do think it’s a fun experience to be able to go to the city without having to have my mom be my taxi driver.

2 Comments

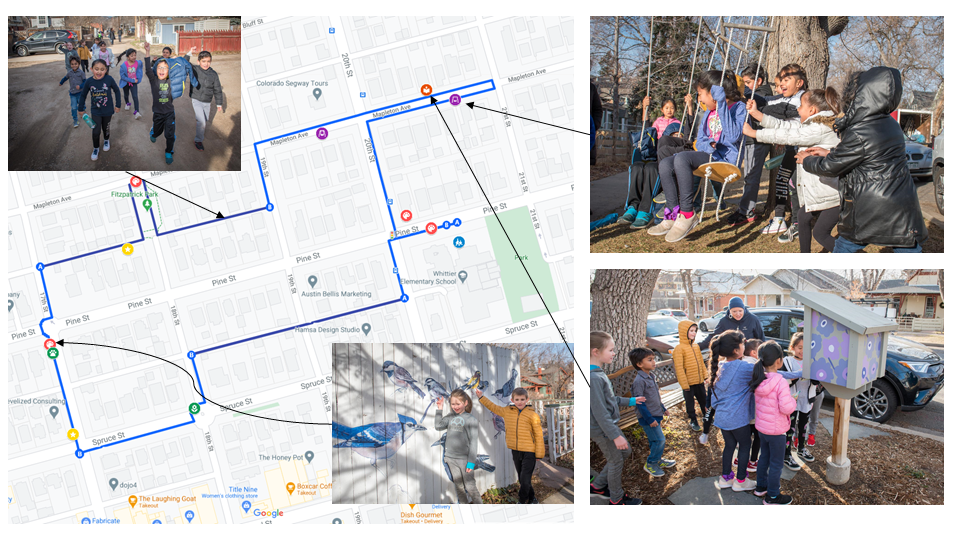

By Darcy Kitching In March 2019, Growing Up Boulder invited me to take a group of first graders on a walk. The class of curious and confident English language learners had helped develop the country’s first child-friendly city map, and I met them at their school to explore a fun walking route we would share with local families in the digital version of the map. Our on-foot exploration led to some unexpected discoveries. My young companions turned out to be urban paleontologists of a sort, unearthing the bones of child-friendly places and an actual dinosaur that sparked my own imagination. As a mother, a child-friendly cities researcher, and an urban planner specializing in walkability, I think I pay more attention than most to the little details that compel people to get outdoors and actively explore their environments, but the 15 first graders I nominally guided on our walk showed me much more than I showed them. As we set out with their three teachers on our one-mile route, I pointed out the “leading pedestrian interval” crosswalk signal integrated into the four-way stop light near the school, which gives people crossing the street a head start when the light turns green. I brought their attention to the wide sidewalks that made it easy for us to explore together, and as we ventured down an alleyway to a pocket park nearby, I asked them to notice the lack of cars and the sense of safety that affords. But the pedestrian-friendly infrastructure in the school’s historic Boulder neighborhood simply allowed us to relax and enjoy the sights along our walk. It supported our real mission: to find out what made this particular area special. The first feature that caught the students’ attention was a metal sculpture of a buffalo in the front yard of a nearby house. They stood beside it for a photo, then ran down the sidewalk to two swings hanging from a tree in the parkway strip of grass between the sidewalk and the street. The students took turns pushing each other on the swings, gushing with enthusiasm. We found other delights in the public right-of-way along our route, including a Little Free Library with a bench for passersby, a tire swing, gardens with places to rest, creative rock patterns, artwork painted and mounted onto fences, and a series of decorative tiles set into the sidewalk. As we turned onto a dirt alley, several of the students ran, chanting, “Mex-i-co! Mex-i-co!” When I asked what they meant, one student told me that the narrow dirt lane reminded her of visiting her family members in that country. Her delight spread, and soon they were all chanting and laughing together. I captured their enthusiasm along the way and led them to what I had thought was the most interesting local feature: a tiny plaza featuring a color-coordinated chicken coop and Little Free Library, with a bench and lots of art. While I adored what the homeowners had offered their community by developing a colorful little resting place in the right of way, it was their flock of silkie chickens and a towering spruce tree that attracted the children. I was admiring the fluffy birds with some of the students when I heard a shout from the tree behind me: “Hey, look - a dinosaur!”  I spun around and saw several children squatting and pointing, holding up the low branches of the spruce tree. I bent down and looked, too. There, in a clearing beneath the tree, was a brontosaurus beaming at us. I realized that, as sensitive as I thought I had been to children’s perspectives and interests in their environments, I never would have lifted up those branches myself. The children happily and without question explored every part of the neighborhood accessible to them, exemplifying the concept Dr. Catherine O’Brien has called “footprints of delight.” With so many enchanting features to explore, it was no wonder the first graders kept walking, running, and even doing gymnastics in the neighborhood park for more than half an hour on our journey with no signs of fatigue or boredom. My thoughts have returned to the dinosaur under the tree repeatedly since my walk with the students. I started reflecting on the dinosaur as a symbol of the hidden charms of the public realm and what it takes to intentionally create points of interest in places without robbing them of their mystery and delight. I thought about other child-friendly walks I had led and the “dinosaurs” the participants had gravitated toward, including art of all kinds, sculptural rocks, pools of shade, interesting places to rest, and even a bike rack that could be climbed through in a way I hadn’t imagined.

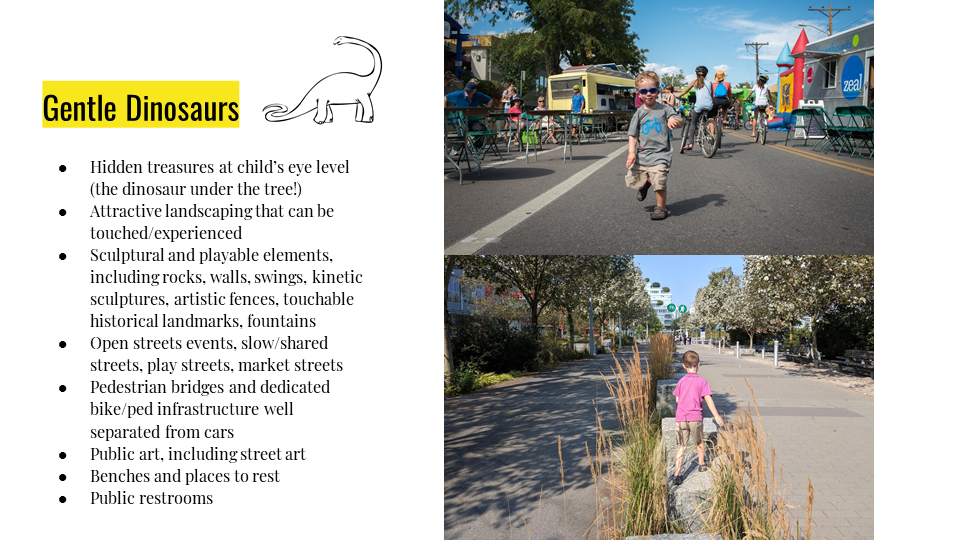

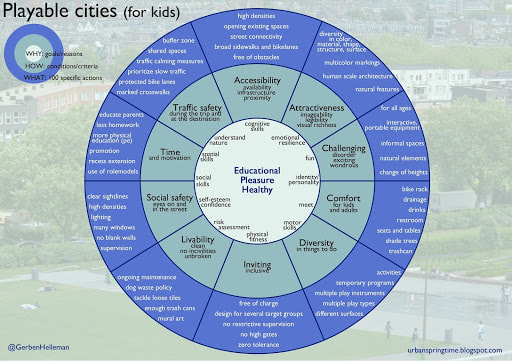

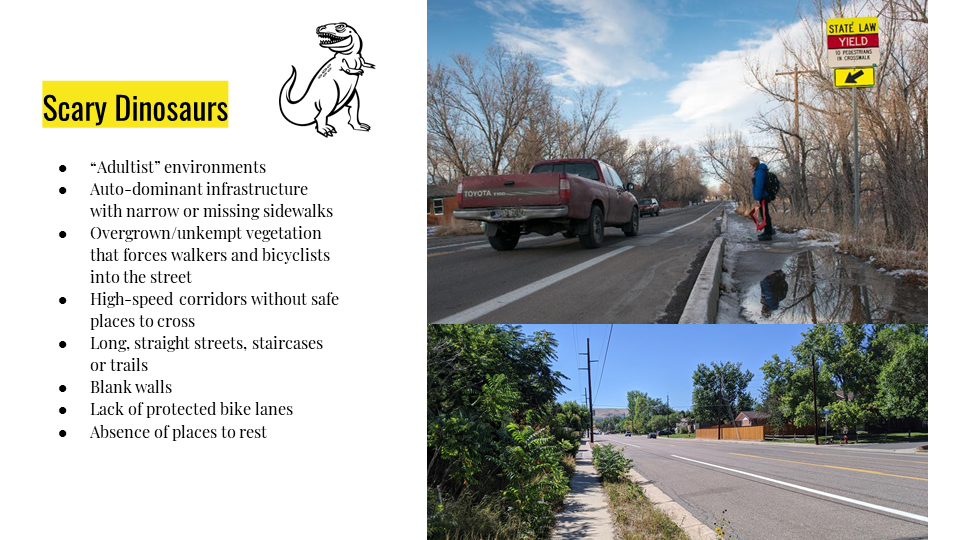

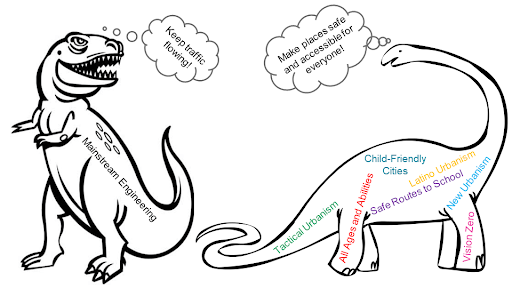

Reflecting on experiences with my 8-year-old son and thinking about principles of creative, people-friendly urban design, I identified both small and sizable “gentle dinosaurs,” from hidden treasures only a person close to the ground could find, to the amenities that support walking, including comfortable places to rest and accessible public toilets. The list above includes eight categories of “gentle dinosaurs” that can be implemented from the bottom up, by artists, individuals, organizations, and municipalities with hands-on community engagement. Even large-scale changes to the public realm can qualify as “gentle dinosaurs” - after all, brontosauri were massive creatures up to 75 feet long! I remembered the downtown Boulder open streets event we participated in when my son was 2 years old (top picture above), which featured food trucks, entertainment, activities, and open space for walking and rolling. And whenever we visit his grandparents in Vancouver, Canada, my son can walk for miles on the wonderfully child-friendly separated bike and pedestrian paths throughout the city (bottom picture above), where wide pathways, natural landscaping and climbable features make walking with a child effortless and fun. For adult caregivers, “gentle dinosaurs” also offer the enormous benefits of reducing stress and inspiring play. Not having to protect children from traffic and other hazards allows us to relax and simply enjoy our time outdoors. Dutch researcher Gerben Helleman captured the essence of such “gentle dinosaurs” in his work on “playable cities.” In the diagram above, he links the benefits of creating playable places with 100 specific actions that inspire and support play in urban environments, including accessibility - the availability and proximity of walkable infrastructure - and amenities that are inviting, inclusive, diverse, and safe. On the other end of the spectrum, “scary dinosaurs” tend to dominate public space in North America, creating decidedly “adultist” environments, as described by researchers Meghan Cope and Brian Lee. “Scary dinosaurs” are characterized by size and speed: they are built for people traveling in cars, attending to distant goals rather than near and present experiences. Like the T. Rex once did, “scary dinosaurs” tend to clear everything in their path, leaving behind inhospitable environments for smaller and slower-moving inhabitants. A few years ago, I worked with GUB and students at a Boulder middle school to identify barriers to walking and biking to school. The students pointed out how the lack of sidewalks, drainage, and safe crossings near the school made it too hard to travel actively. I witnessed several cars and trucks go by without yielding as a student waited at a crosswalk (top picture above). Speeding traffic is an obvious “scary dinosaur,” but the street design that enables it can also be classified that way. Long, straight arterial roads without any designated crossings facilitate speeding and inhibit walking and biking. In many areas, students have to cross the types of roads pictured above (bottom) to get to school, putting them at great risk. Places full of “scary dinosaurs” are also psychologically exhausting. It just isn’t fun or interesting to walk alongside blank walls, on uninterrupted concrete, or in places that lack shade and human-scaled amenities. For people dependent on public transit, walking, and bicycling, “scary dinosaurs” make getting around uncomfortable, uninspiring, and dangerous. Even though “scary dinosaurs” are pretty prominent in our everyday lives - owing to the dominance of mainstream traffic engineering and its goal of keeping cars flowing - there is a veritable rainbow coalition of people and organizations working to increase the presence of “gentle dinosaurs” in American cities and towns. Initiatives such as UNICEF’s Child-Friendly Cities and the international Vision Zero network are inspiring new approaches to ensuring that people of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds can walk and roll safely, in environments that support their well-being.

As those first graders who discovered the brontosaurus under the spruce tree taught me, the supportive infrastructure that makes walking easy paves the way for deeper exploration. Those students felt safe enough to squat down and peek under the tree, to cartwheel in a pocket park, to jump into a swing just a few feet from the street. Slow traffic speeds, wide sidewalks, and places to rest made discovering all of the special things in the neighborhood possible. And neighborhood residents had cultivated a culture of creativity, where just about every property offered something interesting to explore. Ask yourself, “Where are the dinosaurs?,” and go looking for them in your own community. What do you notice? Where might “scary dinosaurs” be tamed and “gentle dinosaurs” be encouraged? We can all breed “gentle dinosaurs” right where we live by inviting creative expression and exploration in the public right of way and working with our local governments and organizations to create child-friendly streets, eventually flipping the proportions of “gentle dinosaurs” and “scary dinosaurs” in our cities. After all, back in the Jurassic period, plant-eating dinosaurs outnumbered carnivores!

Cathy: Teachers are capable, resilient, and adaptable human beings. Even so, going to virtual classrooms overnight is a huge undertaking. Parents everywhere can support their child’s onboarding to online learning by being patient. Teachers are doing their best to re-establish learning and the learning community, and students are doing their best to do what is now being asked of them. Everyone is adjusting. For example, at the beginning of week 2 of online learning, one BVSD teacher shared with me “the training wheels aren’t off yet, but this week is going so much better than the last.” Patience is key. And let’s remember that children look first to their families for guidance and reassurance, and then they look to their teacher. Successful families will have a strong triad of support between student, parent, and teacher. Mara: Cathy, at its core, what is classroom teaching and learning about for you?

Mara: What motivates students in the learning environment? Cathy: Kids thrive on real-world issues and current events that are relatable to them. Project Based Learning (PBL) is a teaching method in which students learn by actively engaging in real-world and personally meaningful projects. Brain research tells us that when kids are emotionally connected to their learning, they experience 11% higher academic success than if they’re not. When teachers create project-based units, they integrate real world issues meaningfully into the standards that they are required to teach. Mara: Could you provide a quick example of what this looks like in the classroom? Cathy: Sure. In my former classroom, a student brought in an article about gray wolves being taken off the endangered list; based on this interest, our class explored the history of gray wolf populations in the US. Students researched both ranchers’ and environmentalists' points of view and debated the issue. We sent letters to the US Fish and Wildlife Service staff to share our opinions on the subject. Paralleling PBL research, students in this example found a great amount of connection, focus, and purpose. They became passionate and self-directed leaders, advocating for their own learning, and they brought their whole selves to the work. Ideas for taking action naturally occured, and they experienced success in every way. Mara: If you were to design a virtual learning space that responds directly to the most pressing needs of educators and kids amid this pandemic, what would it look like? Cathy: If I were teaching virtually today, I’d prioritize 4 key aspects and implement them well. Think of these aspects as concentric circles - starting with the individual in the center, and expanding out into the classroom community, the local community, and then to the furthest reaches: the global community.

Mara: Do you think there’s value in school-wide community projects during COVID?

Mara: Any parting words to the teachers listening in? Cathy: Yes, Mara, one final point. If I were a teacher in the virtual classroom now, I’d be thinking hard about what academic and socioemotional learning outcomes I wanted for my students during this time of virtual learning. Teachers use this “backwards design” strategy to effectively plan--what outcomes do I want? And then, how do I want to get there? When COVID is over, and my students reflected back on this time with me, what would they most remember? What would they take away from the experience? What would they appreciate the most about our time together? Will it be that they learned multiplication, how to write an essay, or facts about some science topic? Or would they most remember the feeling of our welcoming, virtual classroom culture, the inspired teaching and learning despite being apart, or the strong sense of belonging and purpose for learning that we were able to cultivate across remote learning platforms? No doubt, every student will answer these questions differently, but I know what my priorities would be - ensuring that my families were in a good place and developing community at each level. Mara: Cathy, before wrapping up today’s conversation, what resources on our own Growing Up Boulder website do you think would most effectively support teachers, parents and students during the COVID quarantine? Cathy: By visiting our website, growingupboulder.org, you can find an entire section dedicated to our very own virtual resources targeted toward families and teachers. You can also subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media for updates on opportunities to get involved in our current projects that are switching to online engagements. For example, there are great opportunities for young people and whole classrooms to provide input on some of Boulder’s current city planning projects via narrated slideshows, video tutorials, and creative activities. There are also opportunities for young people to connect to each other. Finally, we’ll offer simple ways to keep children, families and teachers engaged, active and positive. Mara: Thank you for taking the time to share your expertise with us today, Cathy. If listeners want to reach out to you, how do they contact you? Cathy: I’m happy to receive emails from students, parents, and teachers interested in being involved at catherine.hill@colorado.edu |

This Growing Up Boulder blog is a place for GUB leaders and partners to share their thoughts about child and youth participatory planning and child-friendly cities. Enjoy!

|

*Growing Up Boulder (GUB) is a nonprofit program leading Boulder's child friendly city initiative. GUB is fiscally sponsored by the Colorado Nonprofit Development Center (CNDC), EIN: 84-1493585. Since 2009, GUB has worked with over 8,000 local children and youth on more than 100 projects and reached more than 2.5 million people globally.

© COPYRIGHT 2015. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.